Convivencia, Reconquista, and Romanticism

For some of my students in my early Islamic history course it is a bit strange when I bring up Spain. To be fair, Spain as we know it today did not exist in the first several centuries after the emergence of Islam and most people generally associate Islamic history with the Middle East, North Africa, and to Central Asia not southern Europe. However Islamic-rule in various forms shaped southern Spain or Andalusia for nearly 750 years. Prior to the Reconquista and Inquisition, Andalusia was home to large numbers of Muslims (Moors), Jews, and Christians, but following Queen Isabella’s conquest of Granada in January 1492, Muslims and Jews were given an ultimatum to convert or leave in the following decades contributing the Christianization of the Iberian Peninsula.

In the 20th century, Spanish historian Américo Castro used the term Convivencia, often translated as “living together” or “coexistence”, to refer to Islamic-rule in Andalusia. The historical narrative of the Convivencia argues that the Moorish rulers of Iberia promoted a form of religious pluralism in which Jews, Muslims, and Christians that was ahead of its times given that tolerance was not exactly common in the Medieval world. While Andalusia’s religious minorities generally fared much better under Islamic-rule than under their Christian counterparts; romanticizing the Convivencia ignores the complexity of Andalusia’s rich history.

Islam came to southern Spain in 711 CE when the Amazigh (Berber) armies of Tariq bin Ziyad crossed the straits of Gibraltar at the invitation of an aggrieved Visigoth noble. Ziyad’s armies would dispatch the Visigoth rulers of southern Iberian Peninsula with relative ease and Muslim-rulers would remain in power for several centuries. When Abdel Rahman II proclaimed his own Caliphate (Islamic empire) in the mid-9th century, Cordoba became a center of scholarship, the arts, and economic might. At the center of Cordoba’s success was a thriving Jewish community that produced renowned scholars such as Maimonides (Musa Ibn Maimon). Today the historic Mezquita Cathedral of Cordoba (pictures above), once a grand mosque turned Catholic Cathedral, reminds visitors of the city’s Islamic past.

The romanticization of this period of Andalusia’s history ignores the nature of the social contract under Islamic-rule. As would be expected, the Muslim rulers of Andalusia (as with their contemporaries throughout the Islamic-rule) privileged the rights of Muslims above non-Muslims. Andalusia’s Christians and Jews enjoyed protected status which included the right to worship relatively freely. As long as subjects paid their taxes, did not blaspheme, and were loyal to the regime, their Muslim-rulers were generally unconcerned with how they worshipped. Muslim Caliphs, kings, and emirs employed Christians and Jews in their court and Christians, Jews, and Muslims all participated in the economic success of Andalusia. However, as with all eras of history it was uneven and disjointed at times.

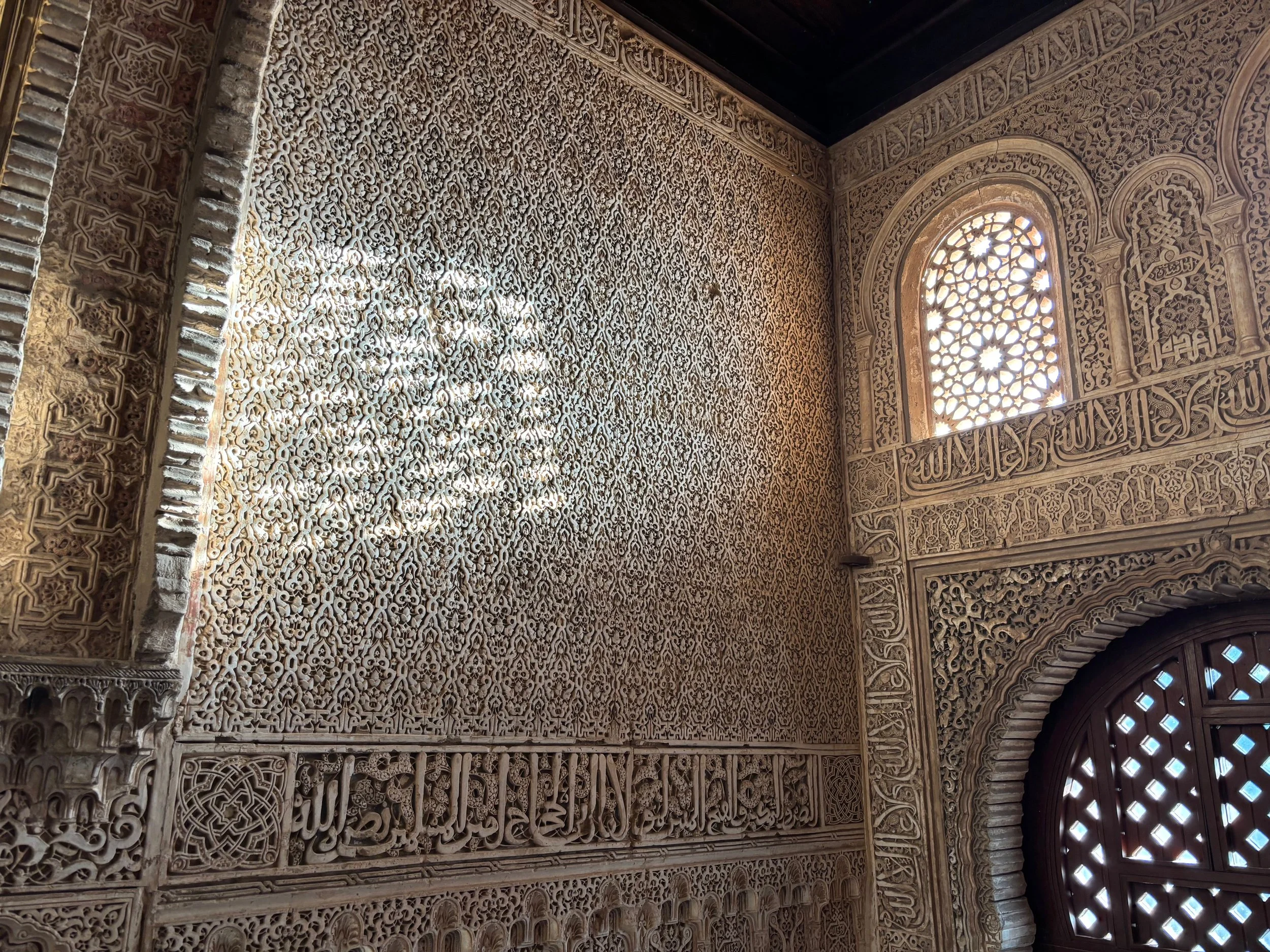

By the early 11th century, the politics of Andalusia were fractured and power no longer emanated from Cordoba. Competing Islamic city-states, or Taifa kingdoms, like Toledo, Granada (famed for the Alhambra palace pictured below), and Sevilla warred with each other and even allied themselves with neighboring Christian kingdoms in their quest for power. The chaos of the Taifa period would be replaced by the fundamentalism of the Almoravid and Almohad dynasties who crossed into Andalusia from North Africa at the invitation of Muslim rulers and decided to make it their own in the late 11th and 12th centuries respectively. The Almoravid and Almohads rejected the cosmopolitan rule of the Taifa states and replaced it with rule that clearly delineated lines between Muslims and non-Muslims. Under the new rulers, Jews and Christians were forced to pay higher taxes and mandated to wear specific clothes distinguishing them from their Muslim counterparts. The romanticized nature of the Convivencia often ignores these episodes in their telling the history of Andalusia.

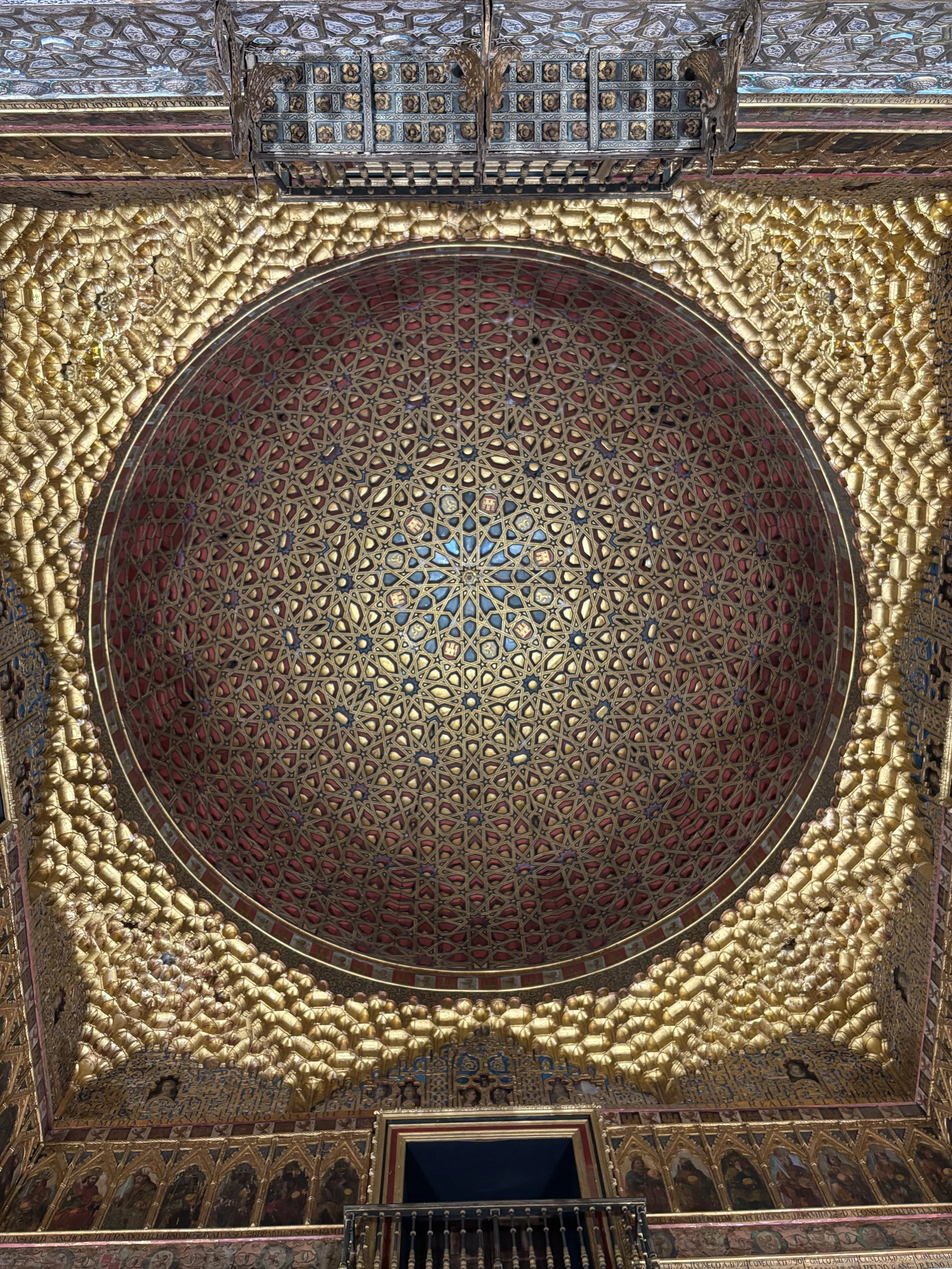

History is many things, most notably the study of the past, but it is most of all contested. In the early modern period, Spanish historians proudly portrayed the Reconquista, the Christian conquest of Spain, as a successful civilizational struggle in which valiant Christian warriors slowly re-established the supremacy of Christianity in the Iberian Peninsula and expelled the infidels. Spanish historians celebrated figures like St. James Matamoros (literally the Moor slayer) and El-Cid while depicting the Reconquista as divine providence and proof of their civilizational superiority. At the same time Spanish rulers repurposed mosques as churches and hired Muslim artisans to craft their new palaces in the Mudejar style.

Both of these narratives of history are problematic and present and romanticization of the past that is still being contested today. Historian Brian Catlos says of this phenomena:

“Sorting fact from tendentious myths and conjecture is crucial, for Islamic Spain is not only an important element in the history of the Mediterranean world, of Europe, of Islam, and of the West, but also remains of great significance today. Many politicians and public figures-and not a few scholars-continue to view the history of the West as one of a conflict between two fundamentally incompatible civilizations: a Christian (or, very recently, Judeo-Christian) one, and an Islamic one,. This view exercises tremendous appeal because of both its simplicity and its self-validating quality, and it is often invoked by pundits and demagogues of all stripes as a justification for aggression and repression. For others, al-Andalus presents an idealized vision of premodern enlightenment that we in today’s supposedly less tolerant world should emulate. But this too is a mirage. In Spain itself, right-wing politicians continue to draw on the ethos of La Reconquista - a potent national myth that conveniently justifies the domination of Castile over the other regions of the peninsula, even as tourist boards promote a sanitized vision of Spain as ‘the land of the three religions’ and of Christian-Muslim-Jewish harmony.”

The simplified and romanticized histories of Spain (among many other histories), which Catlos attempts to debunk in his book Kingdoms of Faith, contributes to the historical illiteracy of the past. The romanticizations of the Convivencia and the Reconquista are both so tempting because they promote idealized solutions while robbing us of the complexities of reality. As much as we may want to harken back to an idealized past, we are stuck with the reality that humans are complex and that human nature has not, nor will likely change dramatically. Racism, sectarianism, bigotry, etc. are not new and are not likely to disappear, nor will militarism, violence, and the contestation of political and economic power. Better understanding how past societies navigated and often failed to navigate these pitfalls will likely better help us to navigate these challenges in the present. Romanticizing the past will definitely not.